Think back to your most frightening memory from middle school. Was it getting bullied on the playground? Was it dissecting a frog? Was it being asked if two trains left stations X and Y travelling at speeds A and B on the same track, what time would they collide and kill all the passengers on board? Maybe your math teacher was sadistic and added in that the trains picked up three times the number of passengers that got off at the last station, etc. Now, you are left not only deciding when these people will die, but what the death toll is.

Whatever your answer, I'll bet if you went to school in the 80's, at least one of you said sentence diagrams. If you didn't, would you like to change your answer? Looking back we might ask ourselves why we did this. What did that teach us about our language?

Whatever your answer, I'll bet if you went to school in the 80's, at least one of you said sentence diagrams. If you didn't, would you like to change your answer? Looking back we might ask ourselves why we did this. What did that teach us about our language?Types of Grammar

This is a subject you will hear me speak about again. There are two approaches to grammar: Prescriptive and descriptive. German and French are notable examples of prescriptive grammar. There is some academic body that decides the correct way to speak the language. Oxford English is of this type. The rules of "proper" grammar are prescribed to be a certain way.

Descriptive grammar, by contrasts, seeks to understand language as it is actually used. Though what we consider "proper grammar" says you cannot end a sentenced with a preposition, this is very common in actual usage. If that construction is in general use and creates writing that is understandable then it is grammatical.

Even the meaning of words can change in this manner. The technical meaning of irony is use of a word in other than its literal intention which creates an unexpected outcome. As Alanis Morrisette reminded us, that is not the common, descriptive use of the word. More often, irony is used to describe the tragically coincidental, the comically tragic and unexpected, or the tragically inconvenient (rain on your wedding day, overcoming a fear of flying then dying in a plane crash, or ten thousand spoons when you need a knife). Though purists will object, the Oxford English Dictionary now recognizes these alternative uses.

Even the meaning of words can change in this manner. The technical meaning of irony is use of a word in other than its literal intention which creates an unexpected outcome. As Alanis Morrisette reminded us, that is not the common, descriptive use of the word. More often, irony is used to describe the tragically coincidental, the comically tragic and unexpected, or the tragically inconvenient (rain on your wedding day, overcoming a fear of flying then dying in a plane crash, or ten thousand spoons when you need a knife). Though purists will object, the Oxford English Dictionary now recognizes these alternative uses.Rhetorical Failures

There is a field of English and/or writing only studied by graduate students in English and understood by fewer. This is known as rhetoric. Rhetoric aims at the effective use of language to create better and stronger sentences. It teaches us that English places focus in a sentence at the end. It explains why passive sentences should be aIt prefers the concise. Most importantly, it recognizes that challenging the norm often makes more powerful sentences.

That is to say, diagramming sentences teaches diagramming sentences, but not writing. It is likely to result in much weaker writing in an effort to meet largely arbitrary grammar rules. Such strict adherence to grammar occasionally results in nonsense (for instance dangling prepositions) up with which we should not put.

These same grammarians setting the rules always recognize Charles Dickens as a master of English literature. However, trying to apply grammar to one particular sentence so famous in Charles Dickens's book robs it of its rhetorical power. (And studying writers would not be able to remark, "If I wrote a sentence like that, my professor would fail me.) Had Dickens followed grammar we would not have the powerful sentence/paragraph I am sure you guessed was coming:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

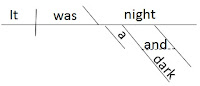

Now I must warn you that what you are about to see is not for the faint of heart. It took me several hours to do this, and I am sure someone will find fault with it. To be honest, I care less now that I am not being graded for my sentence diagrams than I did when I was being graded—which it turns out is not very much in either case.

The Simplicity Test

The main issue with this sentence diagramming is that it complicates what would otherwise be excellent writing. Take a look at this example from NPR, reproduced from pop chart art. Good writing often takes on unrecognizable forms. Even worse is when an instructor says, "Diagram this sentence," and leaves the student staring at the subject portion of a sentence diagram with nothing to put in.

Diagramming also runs into trouble by forcing adjectives into a single position. Ambiguity can add to a piece. These double meanings inherent in words are the key to poetry. Here is a simpler example: Are the eggs alone green or is the ham green as well? We know from the drawing that the ham is also green. Therefore, we must invent a way to diagram this (which is exactly what I did).

Diagramming also runs into trouble by forcing adjectives into a single position. Ambiguity can add to a piece. These double meanings inherent in words are the key to poetry. Here is a simpler example: Are the eggs alone green or is the ham green as well? We know from the drawing that the ham is also green. Therefore, we must invent a way to diagram this (which is exactly what I did).If you lock three grammarians in a room to discuss the sentence "See Spot run," ensure you take all pointy items and possible weapons out. The discussion is likely to end in tears without them. Attempting to show the prescriptive grammar rules in this sentence is nearly impossible. What does the diagram add? The sentence, though not strictly correct, is intelligible. We understand that see means watch or notice here, but rigid grammar will not allow.

What Isn't There

Many teachers feel that students learn to write better by simply diving in. Believe it or not, those same people circling the comma splices in A Tale of Two Cities firmly believe that literature cannot be judged based on the words on the page. We must understand the cultural forces behind a writer's impetus before we can evaluate what he wrote, what he didn't write, and how he wrote it. Diagramming forces students into a cultural paradigm that is not theirs.

Why Do It At All?

Point made; we shall never diagram sentences again. Or are we, as the saying goes, throwing the baby out with the bath water? Originally, sentence diagrams were thought to improve learning by showing how the parts of a sentence work together. English instruction has changed. The terms subject, predicate, direct object, and object complement are used less. You are more likely to learn the terms noun phrase and verb phrase. Some researchers have even begun to question the age-old definition of a noun as "persons, places, things, or ideas." For instance, in English, nouns are the only words that can be made plural. They can be defined by color, number, weight, etc. The same is not true of the other parts of speech.

If seeing how an item works as a learning strategy sounds familiar, it should. Visual learning is one form of learning. Far too little study has been done on whether visual and kinesthetic learners function best by seeing the mechanics behind a sentence. The geometric shapes inherent in this insanity may have value to some learners. Sentence diagramming should remain as a part of curriculum, in my opinion, if for no other reason than as a way to understand the overly strict rules of prescriptive grammar in a visual medium.

No comments:

Post a Comment